Stop me if you’ve heard this one before.

The UK and many other rich countries have set ambitious targets for emissions cuts to tackle climate change, and have already made much headway in recent years. Further progress can be achieved while making sure that fossil fuels are used responsibly, and with promising new technology such as aircraft powered by batteries.

The UK should not do more though, while countries like China and the US continue to emit far more than we do. It’s hard to see why hard-working families should be denied simple pleasures either, like flying on foreign holidays.

In fact, why should we limit emissions at all, since the worst of climate change is already looking inevitable?

If these sorts of claims sound familiar – reasonable even – that’s because they are some of the most common ways of arguing for less ambition on tackling the climate crisis. Outright denial of climate change is becoming rarer, but is simply being replaced by more subtle ways of downplaying the need for urgent and far-reaching action.

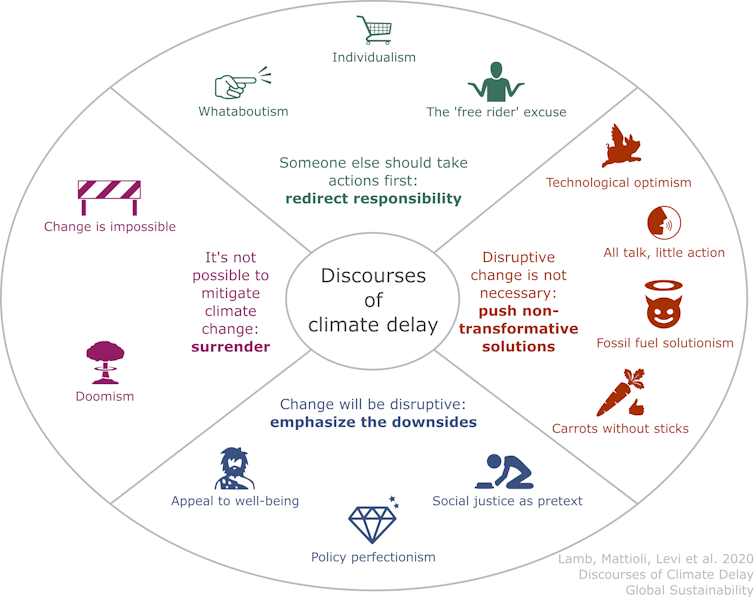

In new research, we have identified what we call 12 “discourses of delay”. These are ways of speaking and writing about climate change that are commonly used by politicians, media commentators and industry spokespeople. Though they shy away from denying the reality of climate change, their effect on the collective effort to respond to it is no less corrosive.

Delay is the new denial

Some of these arguments direct responsibility to others (“what about China?”) or stress the supposed downsides of taking action (“why should ordinary people pay?”). At other times, past achievements or future plans may be emphasised when pushing solutions that aren’t likely to make a dent in greenhouse gas emissions (“we have world-beating climate targets”), or it may simply be argued that it is now too late to do anything anyway (“the climate apocalypse is coming”).

When people make appeals to delay or limit action on climate change, it is often couched in the language of optimism and progress. Take the remarks on aviation by UK health minister Matt Hancock in January 2020. He said that there is no need to reduce how much we fly because electric planes are on the horizon (disclaimer: they aren’t). On the other hand, tackling climate change can just as easily be undermined by a sense of futility or hopelessness in the potential for meaningful action.

It’s important to appreciate that many of these arguments contain at least a grain of truth – and may be used by people in good faith. After all, who hasn’t wondered at some point whether cycling to work instead of driving has much bearing on a vast global problem?

Likewise, it’s not fair to expect those who have contributed the least to climate change to be held back from attaining a decent standard of living. Nor is it reasonable to expect someone in rented housing to pay to upgrade a poorly insulated property in the UK. Genuine concerns about the wider impacts of climate policies become delay arguments only when they are used to downplay the scale of the problems we face, or to obscure the need for immediate and radical cuts to greenhouse gas emissions.

How to respond

By defining the most common delay arguments, we can better understand the obstacles being placed in the path of tackling the climate crisis. They are part of a wider range of stories used to describe climate change that act as important influences on public opinion. They can make the difference between engendering a resolve to act and spreading disgruntled resignation.

A clearer understanding of these arguments also forces us to engage with and find better responses to them. For instance, it’s convenient to view action on climate change as a situation where one country determined to continue polluting can take advantage of the goodwill of others who reduce their emissions. The argument that if I take action it will be exploited by someone else unwilling to do the same (which we call the “free rider” excuse) has been used by the US president, Donald Trump, to pit developing countries against the US on emissions reductions, and to press the case for withdrawal from the Paris Accord.

It is also an argument used to dispute the value of action at the individual level. An emphasis instead on emissions reduction as something for which we all have shared responsibility and obligations – as citizens, communities and countries – is one response to this type of claim. Another is to highlight the opportunities for fairer and better societies that can flourish with the right sort of climate action.

Now that the human hand in climate change is recognised by most people, debate should concern where we are headed as societies, how fundamental are the changes that we need to make, how to compel the vested interests of fossil-fuelled industries to make those changes (whether they want to or not), and how to wrestle with the worrying signs of a changing climate without abandoning our resolve to prevent it worsening. Discourses of delay risk obscuring this essential conversation. We must learn to recognise and answer them with confidence.